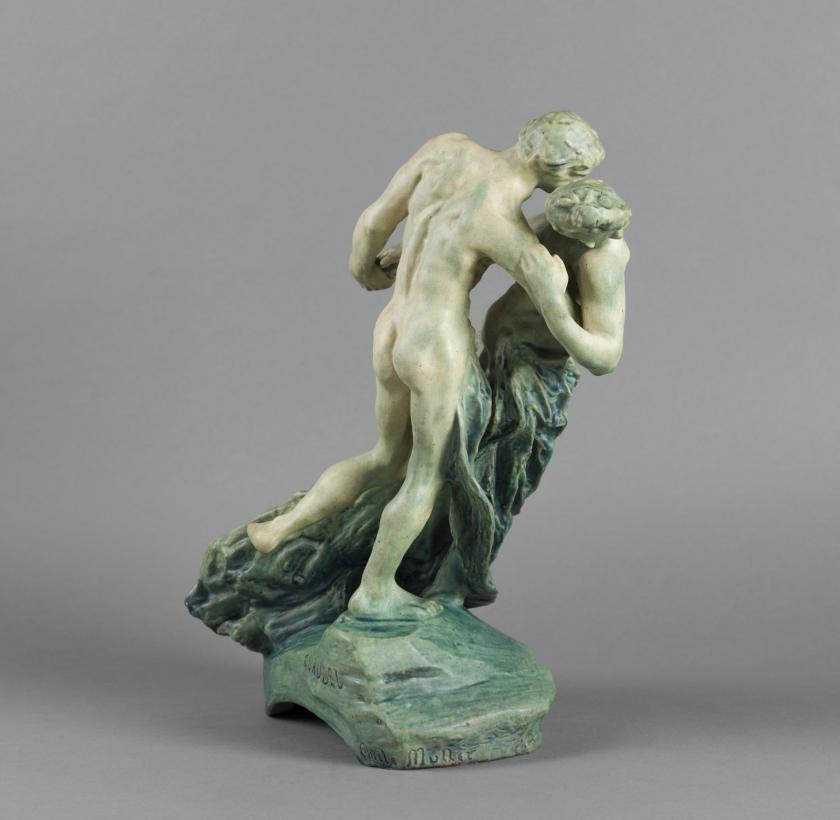

La Valse

La Valse

Emile Muller no14

La Valse (The Waltz) is arguably Camille Claudel’s most famous work. It was conceived between 1889 and 1893 and coincides with a period of intense production and the artist’s passionate relationship with Auguste Rodin.

In 1892, Claudel applied to the State for a marble commission, but the Beaux-Arts inspector refused the first version that featured dancers who were completely naked. To accommodate his expectations, the artist transformed the work by adding draperies, but the transition to marble was unsuccessful.

She then reworked the group and proposed a third version, with fewer draperies, smaller dimensions, and produced in several materials. It is examples of this third version that are presented in the Camille Claudel Museum. Only one of these examples in flamed stoneware has presently been located.

In the 19th century, the waltz was the couple’s dance by excellence and ballroom dancing spread throughout society. However, Claudel was not interested in recounting anecdotes or passing trends. The partial nudity of the dancers removes them from any temporal context and draws them towards a sense of universality. In this respect, the artist adheres to the symbolist trend. The swirling movement of the waltzers and the couple’s embrace embody the concept of a sensual dance. The diagonal of the bodies underlines imbalance, and the skirt accentuates the spiralling movement of the figures. In this way, the next step is already being suggested: The artist thus shows how swiftly the waltz unfolds, drawing the couple into a whirlwind that never seems to stop. With The Waltz, Camille Claudel won the appreciation of many of her contemporaries: “Only an elevated and open mind could have conceived this embodiment of what cannot be seen”, wrote Léon Daudet.

Camille Claudel

After fading into oblivion, Camille Claudel is now recognised as one of the great artists of her time.

She was born in 1864 in the Aisne region of France into a middle-class family and began modelling clay at a very young age, as a self-taught artist. The sculptor Alfred Boucher spotted her talent in Nogent-sur-Seine and became her first teacher. When he left for Italy, he entrusted her to a friend, Auguste Rodin. The young girl promptly joined the master’s studio and for ten years, the two sculptors shared their lives and studios, exchanging ideas, models and influences. Camille Claudel then affirmed her unique style, created a number of virtuoso works and became increasingly famous. After their separation, hurt by the constant comparison of her work with Rodin’s, she asserted her independence as an artist by completely redefining her inspiration. In the midst of mastering her art, Camille Claudel’s creativity was nevertheless thwarted by delusions of persecution. She barricaded herself in, destroyed her works and was eventually committed to a mental institution at the request of her family for the remainder of her life in 1943.

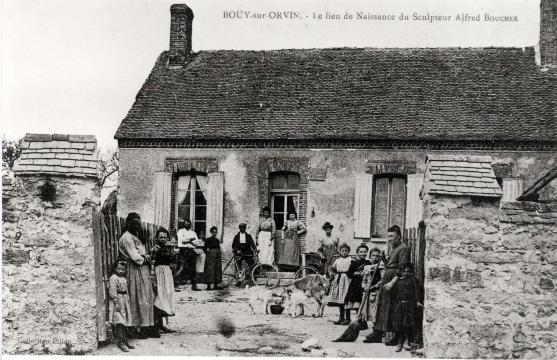

Alfred Boucher

Alfred Boucher was born in 1850 in the village of Bouy-sur-Orvin, approximately ten kilometres from Nogent-sur-Seine. His family moved to this last town in 1859, when Jules Boucher became a gardener for the sculptor Marius Ramus. The young boy discovered sculpture at a very early age and manifested a talent that was encouraged by his mentor. He involved him in creating the decor for the theatre in Nogent-sur-Seine: the young Boucher created a Crayfish fisherman (in the lobby room, a work that has disappeared) and part of the grotesque masks that adorn the façade. Ramus introduced his young apprentice to another sculptor from Nogent, Paul Dubois, who helped him to obtain a scholarship to enter the Beaux-Arts de Paris at the end of 1871. As a student of Augustin Dumont and Paul Dubois, he competed for the Prix de Rome from 1875 to 1879, with his best award being the second grand prize (Jason and the Golden Fleece, 1876). However, he spent a long time studying in Rome, funded by Paul Dubois (1877-1878). During his school years, he met the young Camille Claudel in Nogent-sur-Seine and became her first teacher.

Alfred Boucher exhibited his works at the Salon des Artistes Français from 1874 onwards and they were regularly acquired by the State. A string of successes made him a household name: Eve après la faute (Eve after the fall) (2nd class medal, 1878), Vénus Astarté (classification outside the competition, 1880), La Piété filiale (Grand Prix du Salon, 1881). This last group portrays an episode from Roman history in which the elderly Cimon, imprisoned and condemned to die of hunger, is saved by his daughter who breastfeeds him. The State commissioned a bronze sculpture of the group from the artist, which was his first public commission and his first monumental bronze sculpture. Through the efforts of Jean Casimir-Périer, then a member of parliament for the constituency, the sculpture was awarded to the town of Nogent-sur-Seine and erected between the two bridges over the Seine in 1886. The Grand Prix du Salon also helped the sculptor obtain a grant to finance another stay in Florence, Italy, from 1882 to 1884.

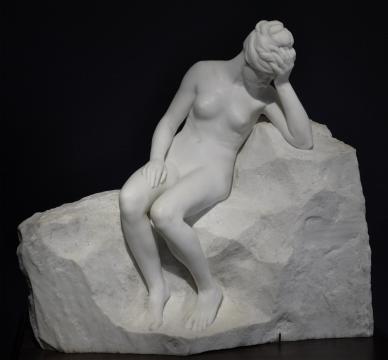

Back in France, Alfred Boucher conceived one of his most modern works, Au But (The finishing line), a group with spectacular momentum that the artist managed to create (1886). A few years later, he continued his work on the male nude depicted in action with the colossal figure of A la Terre (To Earth) (1890), whose pose is directly inspired by ancient sculpture, but modernised by his depiction as a digger. These two works were acquired by the State for the Luxembourg Gardens (bronze sculpture of Au But, now lost) and the Palais Galliera in Paris (marble sculpture of A la Terre). However, his greatest success was with female nudes. The sensual and elegant marble sculptures combine beautifully idealised bodies with a gentle naturalism that brings them to life. Often, areas left untouched or the folds of drapes highlight carefully polished skin tones. The large marble sculptures of the Salon were acquired by the State: Le Repos (1892) and Volubilis (1897) for the Luxembourg Museum, La Pensée (1907) exhibited at the Petit Palais Museum of fine arts in Paris. Countless smaller reproductions of these works were then produced for private customers in various sizes, in marble, bronze and stoneware.

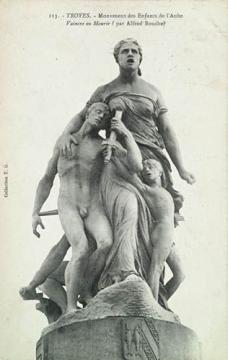

The artist’s highly official career also afforded him numerous public commissions: Monument aux Enfants de l’Aube (Troyes, 1888), Monument to Eugène Flachat (Paris, 1897), L’Inspiration for the façade of the Grand Palais (1900), Monument to Auguste Burdeau (Lyon, 1903), Monument to doctor Ollier (Lyon and Les Vans, 1904)... Private individuals commissioned funerary monuments from him, the most remarkable of which are the allegories on the tomb of Ferdinand Barbedienne (Père Lachaise cemetery, 1894), the mausoleum of the Hériot family (La Boissière-École cemetery, 1901), the Sassot tomb (Nogent-sur-Seine cemetery, 1907), and the tomb of André Laval (Passy cemetery, 1913). He used his mastery of the female nude, both draped and undraped, to create allegories of pain, memory and posterity. After the First World War, his activity diminished and focused on war memorials. He created them by means of the innovative technique using quick-setting cement, for the municipalities to which he was associated: Nogent-sur-Seine, Bouy-sur-Orvin, Aix-les-Bains, where he had been living and working back and forth with Paris since 1885, and, not far from there, La Tour-du-Pin. He also took up painting again, which he had abandoned since the 1880s, producing hundreds of paintings, mainly landscapes and portraits.

Alfred Boucher died on the 17th of August 1934 and was buried in the cemetery of Nogent-sur-Seine, in the grave he had sculpted for his wife in 1913.

Les métamorphoses de l'idéal féminin

Durant la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle, le nu féminin était omniprésent en sculpture. Ce sujet était ancré dans une longue tradition : la recherche de la beauté idéale, caractérisée par une harmonie parfaite des proportions du corps, remonte à l’Antiquité. Ainsi, Alexandre Falguière s’est inspiré pour Ève naissante de l’Apollon Sauroctone (350 av. J.-C.), une sculpture attribuée au célèbre artiste grec Praxitèle. Au-delà de leur capacité à représenter l’anatomie, les calculs savants nécessaires pour déterminer les proportions reflétaient la supériorité intellectuelle des artistes. Cependant, dans le dernier quart du XIXe siècle, de nouveaux canons de beauté ont été reconnus et l’Antiquité n’était plus la seule norme. Paul Dubois s’est inspiré de la Renaissance florentine et germanique pour son Eve naissante tandis que Jules Dalou a proposé une étude naturaliste, sans recourir à l’idéalisation. Et les silhouettes longilignes d’Antoine Bourdelle sont proches des formes végétales avec lesquelles elles se confondent.

Œuvres exposées dans cette salle

- ALFRED BOUCHER (1850-1934), Volubilis, vers 1897, marbre, achat avec le soutien de l’État (Fonds national du patrimoine), de la Région Grand Est (Fonds régional d’acquisition pour les musées), du Département de l’Aube, des Amis du musée Camille Claudel et de Jean-Eudes Maccagno en 2022

- PAUL RICHER (1849-1933), Tres in una, avant 1903, esquisse en plâtre, dépôt du musée d’Orsay, Paris, don de madame Richer et ses enfants en 1934

- MARIUS RAMUS (1805-1888), Première pensée d’amour, 1845, plâtre, don d’Ernest Ramus en 1902

- PAUL DUBOIS (1829-1905), Ève naissante, 1873, plâtre, don de monsieur Dubois fils en 1910.

- ALEXANDRE FALGUIÈRE (1831-1900), Ève, vers 1880, plâtre, dépôt du musée d’Orsay, Paris.

- JULES DALOU (1838-1902), Torse de femme, vers 1887-1889, étude pour la figure de L’Abondance du monument du Triomphe de la République commandé par la Ville de Paris, inauguré place de la Nation en 1879, plâtre, dépôt du musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris, don d’Henri Vever en 1905.

- HENRI CHAPU (1833-1891), La Vérité, après 1890, édition en réduction d’après le monument à Gustave Flaubert inauguré à Rouen en 1890, bronze d’édition, fonte Thiébaut frères, achat en 2003

- GEORGES LOISEAU-BAILLY (1858-1913), Chagrin ou Fille d’Ève, 1902, plâtre, don d’Alfred Boucher en 1913.

- ANTOINE BOURDELLE (1861-1929), L’Aurore (première version sans draperie), 1894, relief conçu pour la façade de la maison Michelet à Vélizy, bronze, fonte Susse frères, épreuve nº4, 1989, dépôt du musée Bourdelle, musée de la Ville de Paris.

- RAOUL LARCHE (1860-1912), Les Violettes, avant 1899, plâtre patiné, transfert de propriété de la ville de Coubron, 2021.

- ANTOINE BOURDELLE (1861-1929), Le Crépuscule, 1895, relief conçu pour la façade de la maison Michelet à Vélizy, bronze, fonte Susse frères, épreuve nº5, 1990, dépôt du musée Bourdelle, musée de la Ville de Paris.

- AUGUSTE RODIN (1840-1917), Bacchantes enlacées, avant 1898, marbre, dépôt d’une collection privée, Angleterre, avec le soutien de la Daniel Katz Gallery, Londres.

La sculpture dans l'espace public

Durant la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle, dans un contexte économique favorable, des travaux d’urbanisation de grande ampleur ont été entrepris en France. Les villes ont été agrandies, embellies et parées de nouveaux bâtiments.

Des fonds publics et privés étaient réunis pour commander aux artistes des monuments sculptés et orner ces espaces. Cette prolifération a été tellement importante qu’on parle de statuomanie. Des groupes allégoriques ou des statues en, hommage aux grands hommes se dressaient sur les places, dans les parcs et sur les façades. Le choix des sujets participait à la diffusion des valeurs de la société libérale et bourgeoise de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle. Pour ce faire, les sculptures devaient être didactiques et le sujet compris de tous. Souvent, les décors sculptés des nouveaux bâtiments publics explicitaient leur fonction, comme Hippocrate et Hygie de Gabriel-Jules Thomas pour la faculté de Médecine de Paris ou L’Âge de pierre pour le Museum d’histoire naturelle.

Être sculpteur au temps de Camille Claudel

Depuis l’ébauche jusqu’à la réalisation finale, l’élaboration d’une sculpture nécessitait l’intervention de plusieurs corps de métiers. L’oeuvre était généralement le fruit de la collaboration du sculpteur, des assistants et des ouvriers spécialisés. L’artiste élaborait la composition de l’oeuvre par des esquisses, puis réalisait le modèle définitif, en terre crue ou en cire. Celui-ci était ensuite moulé en plâtre afin d’obtenir une copie fidèle et solide. Le modèle original était alors détruit et remplacé par le plâtre, qui était présenté au public, lors des Salons annuels ou dans l’atelier de l’artiste.

La sculpture était traduite en marbre ou en bronze seulement si l’artiste obtenait une commande car il pouvait rarement financer lui-même la réalisation de l’œuvre définitive. Les praticiens étaient chargés de tailler la sculpture grâce à des techniques permettant de reporter des points de repères du modèle dans le bloc de pierre. Pour un bronze, c’est un atelier de fondeur qui intervenait.

Handicap mental, psychique ou cognitif

Vous êtes en situation de handicap et souhaitez venir au musée Camille Claudel ? Nous vous accueillons et vous accompagnons dans la découverte des collections et des expositions. Pour vous, l’accès au musée est gratuit, prioritaire et sans attente, sur présentation d’un justificatif. Nos agents d’accueil et de surveillance sont à votre écoute dès votre arrivée, afin de vous apporter un confort optimal durant votre visite.

Handicap auditif

Vous êtes en situation de handicap et souhaitez venir au musée Camille Claudel ? Nous vous accueillons et vous accompagnons dans la découverte des collections et des expositions. Pour vous, l’accès au musée est gratuit, prioritaire et sans attente, sur présentation d’un justificatif. Nos agents d’accueil et de surveillance sont à votre écoute dès votre arrivée, afin de vous apporter un confort optimal durant votre visite.

L’aire d’accueil du musée est équipée de boucles magnétiques. Les audioguides le sont aussi. Des fiches comportant des explications sur les œuvres sont mises à disposition dans les salles. Certains agents d’accueil et de surveillance ont été initiés à la langue des signes française.

Pour les groupes de personnes non ou malentendantes pratiquant la langue des signes française, des visites guidées et des ateliers de pratique artistique peuvent être traduits sur réservation (accessibilite @ museecamilleclaudel.fr).

Le Jardinier Louis Gabut de Boeswillwald de retour en salle

Alors que nous célébrons aujourd’hui les 150 ans de la naissance de son auteur, ce grand tableau d’Émile Artus Boeswillwald a été intégré au parcours permanent du musée.

Grâce à différents dons et legs, le musée Camille Claudel conserve 36 tableaux et dessins de cet artiste dont la famille possédait une maison à Nogent-sur-Seine. Légué à la ville par Hippolyte Fournier en 1909, Le Jardinier a été choisi pour cet hommage en lien avec la thématique de la salle, consacrée aux représentations du travail.

Cette scène de genre figurant Louis Gabut, jardinier et voisin de l’artiste, s’inscrit dans une série de portraits de proches du peintre représentés dans les activités de leur vie quotidienne.